-

Making a VERY long shopping list

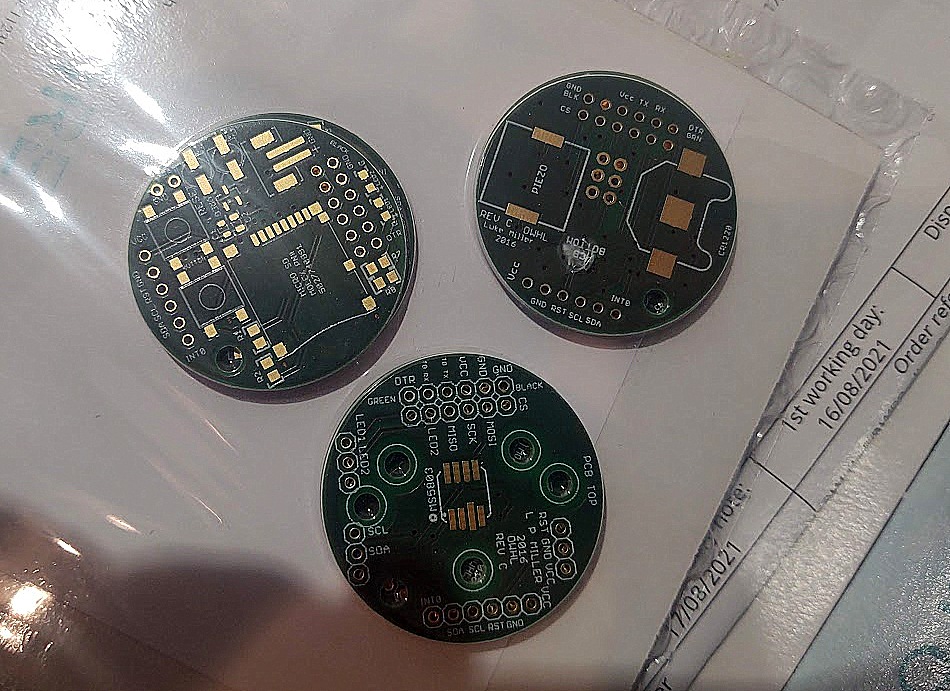

You see even if the project looked legit, and it had a sea-grant from MIT (that MIT) I really did not know where to start. The pages were describing soldering electronic elements I did not even know the names of. Googling in this case could not help. I contacted some old university friends, most people were busy with family life these days, so I reached out to my climbing friends. One of those people was Candice, a Canadian doing her Ph.D. studies in plasma physics here in Norway. (Yeah I know it sounds totally cool, plasma physics). Candice proved to be extremely helpful. She decided she can just sit down ad prepare the BOM (Bill Of Materials) – what they call the shopping list in the PRO world. The BOM was basically a spreadsheet full of cryptic labels indicating different components – such as “ERJ-6GEYJ102V” for a resistor of 1 K Ohm, or “ATMEGA328PB-AU” for the processor. The list consisted of 50 of them nicely arranged into 3 different parts – the sensor one, which should read the water pressure, the CPU one that should do all the “thinking” and finally the power board, which should store the data in the memory card and yes, power the whole device. Each part was a PCB “Printed Circuit Board” basically a board with already printed paths that would work as wires and connect all 50 elements of the whole sensor together. But back then I did not know much about this – I did not even know that one can order and print one, or that companies producing the boards even exist. Candice showed me that the project contained so-called “gerber” files, a fancy name for a technical design of the board. And that I can contact companies like “Beta Layout” and order my board.

To ppl like me, with only basic electronic knowledge (like yeah, I do know the current exists and I needed to learn how a semiconductor works as part of my CS education, but that’s roughly it), the electronic world was funky and cryptic to say at least.

Even with the complete shopping list done for me, placing an order was overwhelming and a daunting task. To make it even worse I did my shopping in the middle of corona lockdowns, which combined with the component crisis made the task even harder. More often than not the parts I ordered would end up in a “backlog” list *waiting list – with up to 2 years of waiting time… Difficulties with orders forced me to become creative and search for the missing parts at AIiExpress or eBay kind of sites.

When the first batch of ordered goods- freshly printed boards arrived, still sealed in protective plastic – things started to look real…

-

Discovering that OWHL exists

Corona lockdown became much longer than anyone expected, the offices did not reopen and the thought of spending winter in total isolation seemed very gloomy. Luckily during the last surf trip, I discovered a co-working place, conveniently situated between the main surf beaches of Lofoten Unstad and Flakstad – the Arctic coworking lodge. The company I worked for had a flexible policy allowing us to work from “anywhere in Norway”, I took it quite literary and I drove all the way up North. (to my boss at that time: “Danke Volker!”)

Tutaj make a map

At that period I was pretty obsessed with the wave forecasting idea and I was willing to discuss it with anyone that would listen. One of those random talkers was a marine devices technician from Oslo – Magnus. He drew me a picture with a water pressure sensor located at the bottom of the surf zone that by measuring the pressure of the water column above – would allow estimating the wave height. That was exactly what I search for. Any forecast can’t be judged without the right observation – in this case, actual wave height! The common surfer wisdom tells you about overhead and double overhead waves – the only point is – the accuracy of such “measurement” is expressed in [sh] units (surfer’s heads), sometimes in non-standardized surfer bodies and it was tricky to convince any surfer to show up in really bad waves weather 🙂 . I did what I was doing so far: googling the water pressure. I googled https://owhl.org/.

Finding an open source – do-it-yourself kind of project was super exciting to me. That was the last piece of the puzzle I needed. The only issue was – I did not even know where to start…

-

How this all started

I was attracted to surfing since a while; I had a classic start by taking beginner lessons on one of the crowded Portuguese beaches. I got a new job and moved to Norway, at first worried about cold water, but after a visit to Stavanger, my hopes grew. A new job and new life in Oslo basically made driving 1.5 – 2 hours each way to surf beach not realistic. In 2020 the corona epidemic broke up, and we were all told to work from home which meant my working hours and what I would call “office” were much more flexible. Unlike gyms beaches in Norway were still open.

Oslo is not the best place to start, the internet and YouTube became my ” surf school”. Learning how to pop up was much less of a problem in comparison – to “but when will there be good waves?”

One of the channels The Surf Rat was particularly inspirational. Tom was explaining that with the progress of civilization we lost our ancestor’s skill of reading the weather. As a new generation, we ended up with ready-made forecasts, so processed that it did not longer resemble the origin. He compared it to a chicken nugget that no longer resembles the flesh of a chicken. Similarly, people relying only on forecasts app gave up on observation skills and lost knowledge to understand natural phenomena. I got intrigued and decided to learn more.

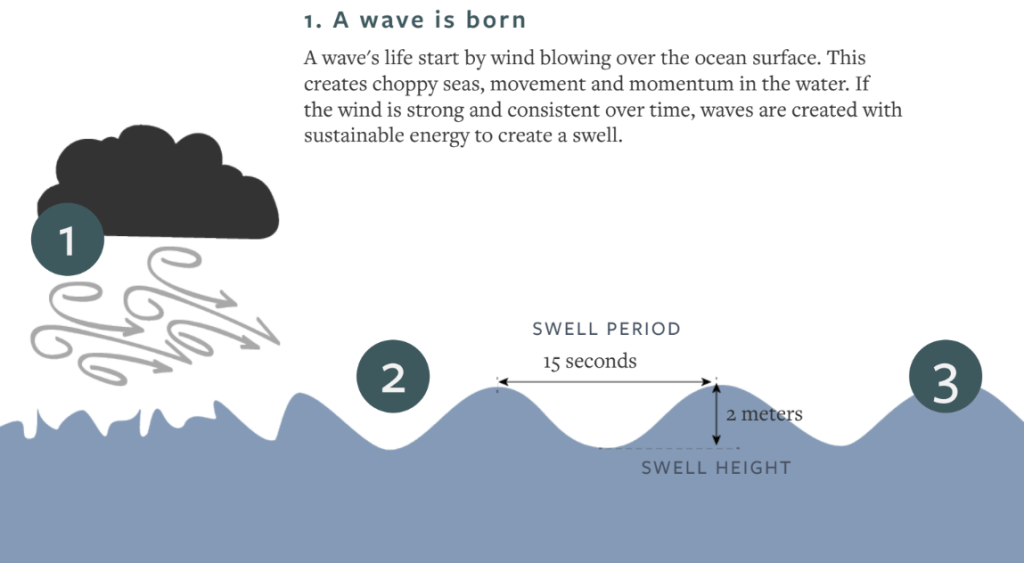

The wave story that you have most likely seen:

classic picture describing wave creation [courtesy of Håkon Jor L’orange] The simplified story, presented in almost every surfer magazine is that somewhere in the ocean a big storm happened, and strong winds created the “fetch area” in which waves were born. Waves then traveled long distances to the shore, depending on the more or less scientific versions of the story they would group and order – creating sets, and then, when they will finally reach the shores, they would start to grow in the shallow water to break in the surf zone. The moment just before the breakup is the 5 minutes of the joy of a surfer. The story also mentioned sometimes that the waves can be “measured” by somehow mysterious “wave buoys” located somewhere out in the water, and based on those measurements the forecast is made. Back then I knew nothing about turbulence, local storms, island, or currents that can make the whole story so much complicated, blissful ignorance can be helpful at the beginning.

I read some articles and even did some training on “how to read surf forecast”, just to conclude that most people do not even know how to read it. Equipped with my new knowledge, together with a newly bought hard surfboard (I did not yet know the board is way too heavy to start) I decided to give it a go and I started showing up at the local beach, making observations.

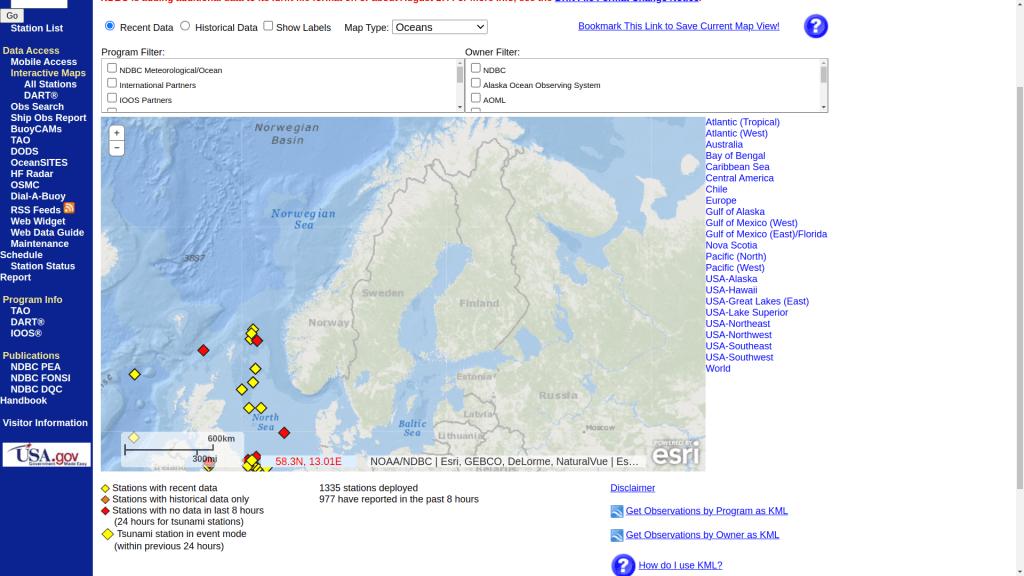

I would take a print screen of the forecast, a photo of waves, check the wind, and sadly conclude there was not much correlation. I asked around – some people would check DMI (Danish forecast), but that was basically it. Obviously, something was wrong with the forecast. Ok “where are those wave buoys” I started to wonder. There must be some way to get the data and check how is that possible.

After heavy googling, it turned out that there are not many, for sure no wave buoys close to my surfing beach, and very few in the Norwegian Sea. In addition, most of the wave boys were located close to … oil platforms … not surf beaches. There was another issue- many of those wave buoys were simply “too close” to rely only on this information to forecast. The time between passing the boy and reaching the shore was simply too short to make a useful forecast – few people would be interested in a forecast 1 hour ahead. If so how can the whole forecast even be done? I realized there must be something more to the forecast than the common surfer wisdom about marine wave buoys. I started to dig deeper (read google) and I discovered Copernicus Maritime and MetEd, then I discovered that global forecasts exist, that the data is publicly available and that surfing forecast webpages is basically wrappers for that data.

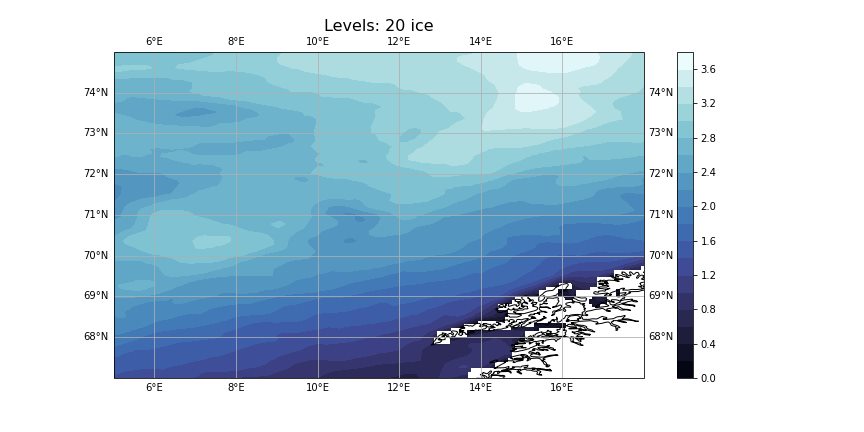

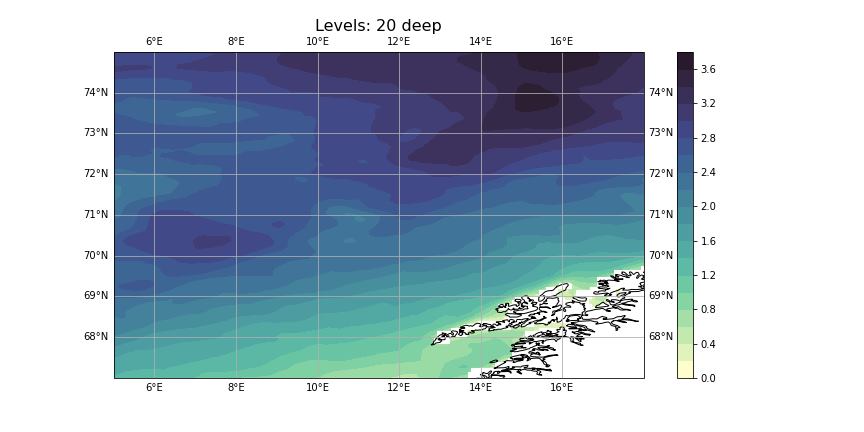

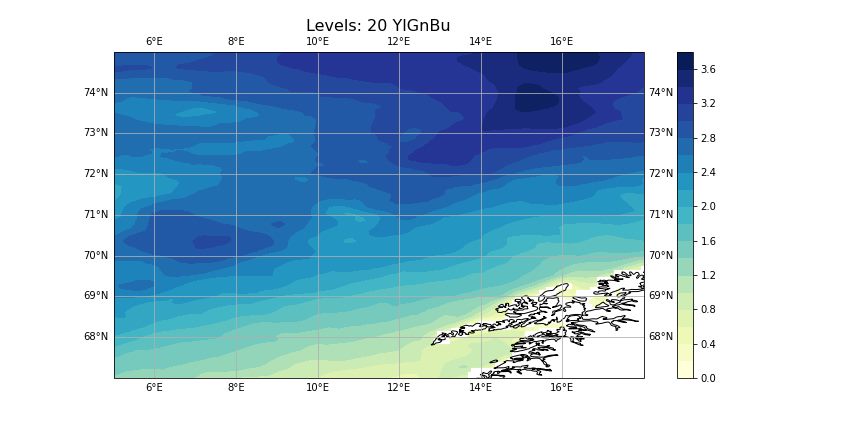

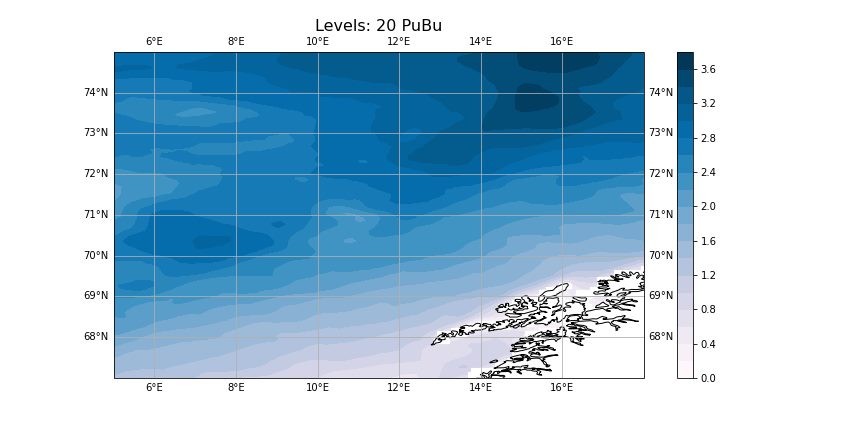

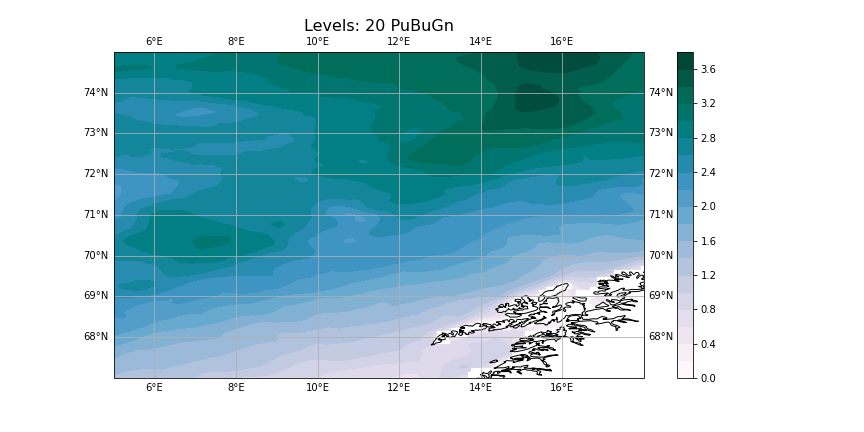

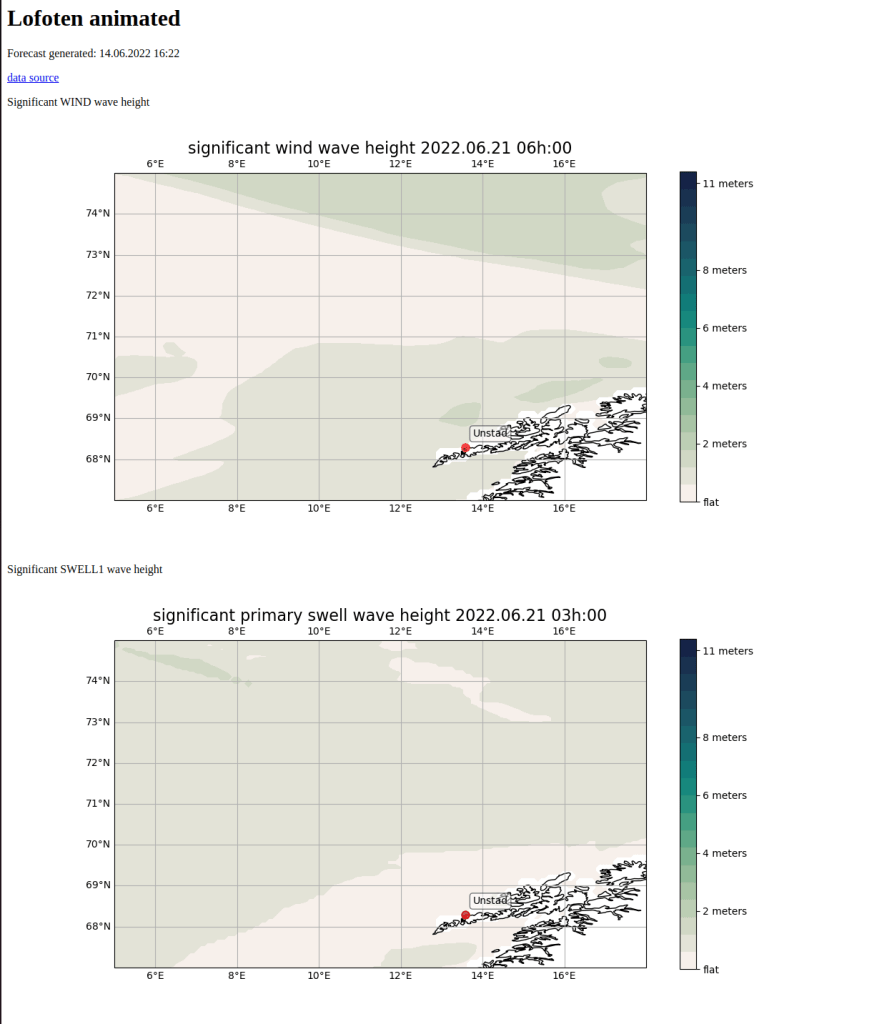

tutaj add pohtos of generated forecast

Screenshot of one of my first visualized forecasts. I was visualiz

ing NOAA data and using Cartopy library

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.