There is a difference between swell and surf. Surfers know that only some beaches break, and under some conditions. Geeky surfers know that it depends a lot on the bottom: the shape itself vs what the bottom is made of (sand banks, coral reef or rock?, it makes a difference). To make the surfing forecast is not enough to have accurate incommoding waves and wind forecast, but

But how do you know that?

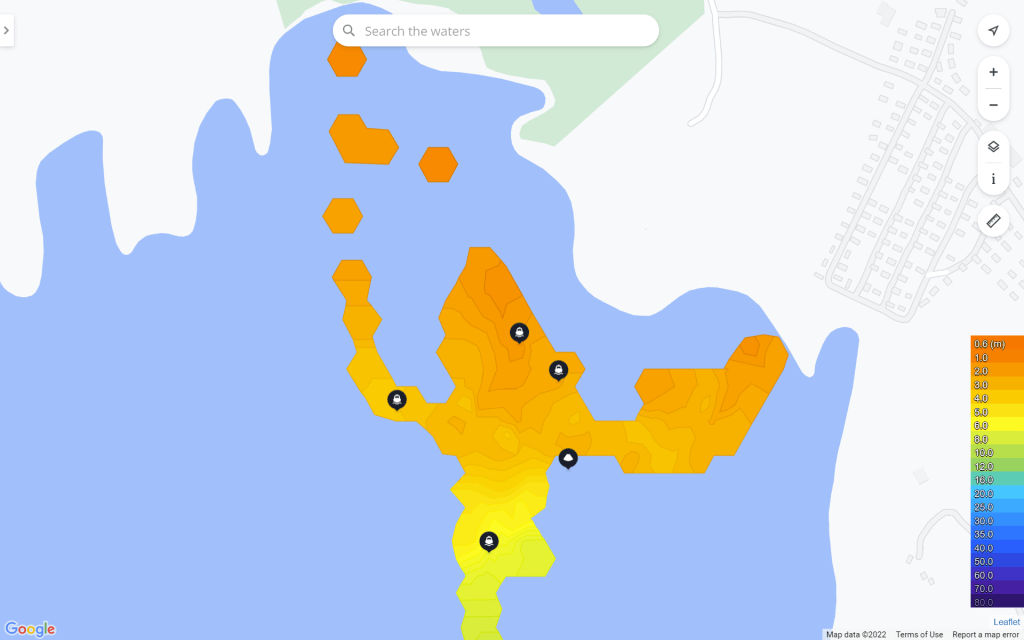

You can read from the map – easy. When you open the maps, the resolution would be around 1 m or less. Not detailed enough for any decent forecast. Back then I did not know that for national security reasons detailed maps of the bottom are not published – the law regulates it. There is another option. Stefano – an Italian guy with who we quarantined together when we both got corona in a surf hostel in Portugal – taught me about figuring out depth based on satellite pictures. You choose an image taken on a sunny day, with possibly no clouds. It’s possible to figure out the depth of water just by judging the shade of “blue”. Observed from space shallower parts of the ocean are lighter, and deeper is darker. To get precise numbers one needs a “color map” first. A color map is a scale – where in this case different shades of aquatic blue correspond to depth.

Of course, this method is as good as the bottom is uniform, but that’s another story. From a work friend Andy, I borrowed a fish sonar and I decided to measure the bottom this way.

I spent two wonderful days kayaking, doing measurements, and taking pictures. I used a cat phone, which was waterproof, but I still was ultra-cautious about water, so the phone was packed in a plastic zip bag. There was one moment when one spoon of salt water got into the phone’s extra plastic cover – but the phone was working well so I ignored it.

Until I came back to the car and tried to recharge. The phone full of data would not charge and it was already only 4% battery left. In a hurry, I uploaded as much data as I could till the phone finally died and I was left feeling helpless.

So what happened? The phone was waterproof right? Yes. But there is a BIG difference between waterproof and salt waterproof. The video below explains it very well. You see saltwater obviously contains salt and “dirt”, making it more conductive. This saltwater layer can act like an extra cable – connecting elements that should be isolated, and if you are very unlucky, creating shortcuts that could destroy sensitive parts. Moreover, salt water is very corrosive – will turn metal (think about metal charger parts) into rust – a thin layer that will prevent you from charging.

That made me realize I was doing all my tests wrong! I was testing for the leakage using tap water! Tap water i s n o t saltwater.

I was lucky this time. I had smart friends who gave me good advice and after flushing my phone with alcohol and storing it in rice – it woke up. The speaker was damaged, and the charger would charge only on one side, but it worked and all my data was safe.

The whole experience made me realize: I was doing all my test wrong! I underestimated how strong and damaging salt water is! For all my leakproof tests I did use fresh, tap water. The rubber elements can be fine with tap water, but salt water is another level. I decided I need to take simple buckets of ocean water and test it in conditions as real as possible. Salinity is a fancy term for “how much salt is in water” – it varies in waters across the globe, and it varies with depth and season. To make your test really realistic – I should use possibly ocean water, extra saltier. This step would be necessary to make sure the device is really TOUGH. In addition, I was considering covering my electronics with an extra layer – just in case some water still gets inside. In most simplitic case – simply several coats of varnish can actually protect the electronics from few drops of salty water. In more serious case – conformal coating would be needed. The main point was to prevent possible shortcuts that could burn some elements.

All those considerations proved to be actually valid. I was testing the device in various conditions – one day few droplets actually got inside. I only needed to replace the power cable – all 3 boards survived – due to what I believe extra coating

But being watertight is one problem – another is pressure resitance. The device would be deployed sever meters under water. The pipes I used were conforming standard – PN-10 or PN-16 thus withtanding pressure of 10 to 16 bars (roughly 100-160 m depth).

Another weak point that I wanted to eliminate was thread connection. Flange are much more prone to pressure. That’s the advice I got from a Portuguese diver Hugo.

atutaj add sateliate photo

Leave a comment